once upon a time i lived on mars, by kate greene

Historically, much of Earth exploration has been rooted in colonialism and subjugation. What kind of remnant legacies and unexamined assumptions thread through today’s discussions to colonize Mars?

Historically, much of Earth exploration has been rooted in colonialism and subjugation. What kind of remnant legacies and unexamined assumptions thread through today’s discussions to colonize Mars?

history is what it is. it knows what it did.

Last Thursday, Jeremy asked what it would take for us to decide to cancel or postpone our planned trip to Australia. On Monday, we rescheduled our flights. Yesterday, the public schools and our kids’ school all closed. In grocery stores, people are calm and brave, Londoners during the blitz. Online, we take turns being scared and comforting one another.

I’m sitting on my back deck drinking coffee with Jeremy. The gardens are full of birdsong. Hummingbirds are having fierce air battles over the shrubbery. And now I know why the pair of crows I’ve been trying to befriend have been so preoccupied. They’re building a nest.

“You know those books that you can’t stop thinking about, won’t shut up about, and wish everyone around you would read? The ones that, if taken in aggregate, would tell people more about you than your resume?” Yeah, I do. Here are some of mine. (I’m going with the obscure ones. If you haven’t already read Dark Emu and The Body Keeps the Score, go, do.)

Nuclear Rites (1996) – Hugh Gusterson embedded himself as an anthropologist at Lawrence Livermore National Labs. He talks about bomb tests as rites of passage for the weapons scientists, and I find myself thinking about this whenever I think about douchebag VCs investing in horrorshows like Uber. A Cold War kid, I saw The Day After on TV and followed the news trickling out of the Chernobyl disaster. I couldn’t conceive of why anyone would build such fucking appalling weapons. This book helped me understand, at least a little.

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down (1998) – I constantly quote Michael Frayn’s “In a good play, everyone is right.” This is a book-length version of the same idea. Her doctors had one framework for understanding Lia Lee’s epilepsy, and her Hmong family had another. However kind and well-intentioned Westerners think we are, when we tacitly assume the superiority of our version of the truth, children die.

Depression: A Public Feeling (2000) – This book introduced me to “political depression”, the idea that anxiety and grief are a wholly reasonable reaction to the destructive and hypercompetitive economies in which we are forced to live. The first chapters are a poetic memoir of one of the author’s depressive episodes, and I find myself reading them over and over. I’ll always be grateful that Ann Cvetkovich gave me a way of thinking about my relationship with my landscape of origin as a settler seeking to right the wrongs of the past.

The Language of Blood (2003) – A wrenching memoir that changed the way I think about transracial adoption and motherhood. If you like it, see also All You Can Ever Know.

Mother Nature (2005) – An anthropologist and primatologist considers the evidence for how best to raise children. A book of radical kindness. If you like it, see also A Primate’s Memoir.

Postwar (2006) I’ve called this the missing manual for Generation X. It provides the context for the political climate in which we were born – the fading of the postwar consensus and peace dividend, setting the stage for the attack on social institutions by Thatcher and Reagan, and the collapse of the social contract that brought us to where we are. You’re not going to like this book, exactly. It’s hard work and heartbreaking. Judt died before seeing his worst fears fulfilled, but if you want more, his student Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands is basically the prequel.

This House of Grief (2014) – Another dumb joke of mine is that Mad Max: Fury Road is a keenly observed documentary of my childhood. This book is, however, a keenly observed documentary of the middle-class Australia in which I grew up, its lonely and angry men, its frightened and angry women, and the horrors it inflicts on its children. In some ways it’s the distillation of everything I’ve talked about here: the slaughterhouse of empire, and ways in which it drains our private lives of meaning.

Horses in Company (2017) – Lucy Rees, who wrote some of my favorite pony books when I was a child, has spent the intervening thirty years catching up on new science around equine ethology. Much as alpha wolves and cocaine-addicted rats illustrate the stress of being an experimental subject rather than authentic wild animal behavior, the received wisdom about dominant and submissive horses reflects domestic animals under resource constraint. Rees argues that wild horses, who can eat the grass beneath their feet, live in the real-world version of Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory, and that in this state of nature they’re feminist matriarchal gestalt entities. I jest, but only a little. If we could take violence out of the way we interact with animals and children, maybe we could take it out of the way we interact with one another.

It seems unfortunate, but nothing was learned from the Chernobyl disaster.

even today we do not know which of the strategies the Soviets tried and the technical solutions they implemented actually worked. Could some of them have made things worse?

…atrocities such as the Rape of Nanking can be seen as a predictable if not inevitable outgrowth of ceding to an authoritarian regime

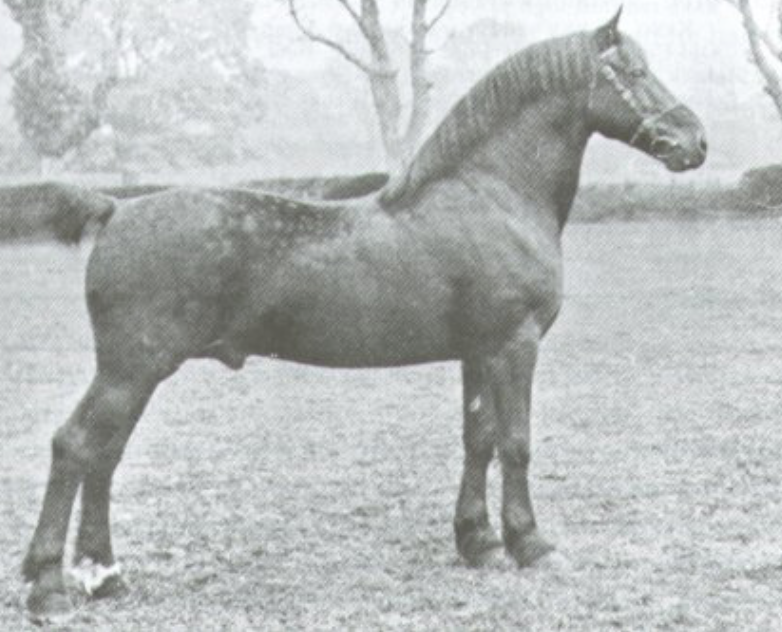

Last night I read and enjoyed Wynne Davies’ The Welsh Cob, described in Amazon reviews as “for cob enthusiasts only”. (I feel seen.) While there have been horses in Wales since pre-Roman times, the purebred cob, an absolute unit, is a surprisingly late invention. The first Welsh stud book was published in 1902, following a busy late 19th century of outcrossing native Welsh ponies with Thoroughbreds, Arabs, Hackneys, Norfolk Roadsters, and Yorkshire Coach Horses.

King Flyer, b1894

At almost exactly the same time, my old friend Lady Anne Blunt was importing Arabian horses to England. The modern Arabian and the Welsh Cob were modeled on the English Thoroughbred, itself a literary fiction. Horses, obviously, exist, but purebred horses exist only in books, beginning with the General Stud Book of 1793. The GSB represents a cartel of Thoroughbred breeders and owners. Only horses registered in the GSB can race on the flat in Britain. A closed stud book raises prices by creating artificial scarcity. (Because of the risk of fraud, Thoroughbreds can only be registered if they are conceived by “live cover”, rather than artificial insemination, a quirk of history that keeps a lot of Thoroughbred stallions very busy.)

The GSB is almost exactly contemporaneous with the United States of America, and both of them pre-date Burke’s Peerage, the stud book for British humans. Nations are also literary fictions. Different rules apply to those whose names are written down in the right books. The white colonists needed a reason to argue that while they deserved liberty from oppression, their slaves did not. They found it in the invention of race. White people, like Thoroughbred horses, counted. They were counted. Black people, like half-bred horses, counted for less. Purebred horses were invented in part as a way to make this appear to be a law of nature: but it isn’t.

Last night as I was drifting off to sleep, I thought about Frenchs Forest, where I grew up, and the tiny pieces of bush that I knew so well: the undeveloped block adjoining the high school, which is now the Northern Beaches Hospital; the little steep park around the corner from our house, called Blue Gum Reserve; and the steeper gully leading into Bantry Bay, which is now part of Garigal National Park, named for the traditional custodians of the land.

Liz has been talking about BART stations through time, and for a minute I could see all those little remnants joined up into one vast sea of dry sclerophyll woodland fading into the blue distance. There were sandstone boulders and shady overhangs. Banksias and grevilleas grew brilliant and spidery in the understory. It smelled like eucalyptus trees under the hot sun and sounded like cicadas singing. This was my home country for tens or hundreds of thousands of years, before the houses were built, even before special constable and crown lands ranger James Ffrench clear-felled the forest that now, in ghost form, bears his name.

I realized that the high sandstone flats, in Allambie and Narraweena and Beacon Hill, are carved and were likely ceremonial. People would live closer to fresh water, I thought. As I traced in my mind the clear cool creeks (Frenchs, Carroll, Bates) that run down into Middle Harbour, I realized that the rill that ran across the bottom of the high school oval and into Rabbett Reserve (willow trees and golden sand, frogs and tadpoles) ran the other way, into the confusingly-named Middle Creek. My home was high on the watershed itself.

Middle Creek flows not into Middle Harbour but into Narrabeen Lagoon. According to the Dictionary of Sydney:

The camp site at Narrabeen Lagoon was the last community Aboriginal town camp to survive in the northern Sydney suburbs. Probably, before the British invasion, Narrabeen Lagoon was one of the many coastal occupation sites offering seasonal shelter, fish and wetland resources… higher and less accessible country was used for ceremonial and educational purposes by the Gai-mariagal. Dennis Foley, a Gai-mariagal (Camaraigal) descendant, describes the area as ‘the heart of our world’.

Dennis Foley has written of the destruction of the camp in the 1950s, when what became the Academy of Sport was built. When I was a child in the 1970s, it was whispered that there were still people living there. These were the survivors of the genocide of the Eora people. There is no sign or memorial.

I’ve been thinking a lot about gods and goddesses and the dead: la Calavera Catrina and Guadalupe and Epona, all psychopomps, all syncretist beings like me. I’ve been thinking about AORTA’s Theory of Change:

Decades of neoliberal policy have erased histories of enslavement and genocide, and the movements that fought and resisted along the way. Today’s social movements are often disconnected from local, regional, national, and global movement history, which can lead to a sense of isolation and alienation.

And about this essay, in which:

Derrida asked, ‘Is it possible that the antonym of “forgetting” is not “remembering”, but justice?’

Gods and goddesses move around outside time, where the dead are not gone, just elsewhere. Historical memory is a kind of augmented reality, a map drawn in the colors of love and grief and anger. May I honor the memory of my dead. May they seek justice through me. May I be a good ancestor in my turn.

I’ve had the Split Enz song “Six Months In A Leaky Boat” on constant replay this trip. I wasn’t at all surprised to find out Tim Finn wrote it after a nervous breakdown. I complained to Jeremy that everything I want to say about the legacy of settler colonialism and consequent mental illness, this song says in five minutes.

Aotearoa, rugged individual

Glisten like a pearl, at the bottom of the world

The tyranny of distance, didn’t stop the cavalier

So why should it stop me? I’ll conquer and stay freeAh c’mon all you lads, let’s forget and forgive

There’s a world to explore, tales to tell back on shore

I just spent six months in a leaky boat

Six months in a leaky boat

An old friend tried to argue that Doctor Who isn’t a modern King Arthur myth because “no one cares that much about stories.” And yet it moves. In case you’re not convinced that this song is a miracle of subversive irony, I’ll just point out that Thatcher banned it during the Falklands War.

The defining feeling of my childhood was that of being told there wasn’t a problem when I knew damn well there was.

Against its nature, the terrified prey animal is turned into an incarnation of terror which drives the predator, man, to flee

The horse was born not in Troy, but in Alexandria: it is a phantom of the library

The connections forged between humans and horses nowadays are relationships based on love, communities of interest and sporting camaraderie.

the native language of equine history is Arabic.

Nobody would have noticed the waif-like boy who hung around the Paris horse market for days on end, in 1851 and the following year. Confident that he was unobserved, he scribbled away on the notepad he took everywhere with him, like a painter on his travels. Nobody recognized him as a young woman dressed as a man, pursuing her ambitious plan.

girls and horses are islands in the flowing river of time.

Somewhat like a precursor to cybernetics, only more direct: a neuro-navigation between interrelated natures. Two moving, loosely coupled systems, circumnavigating the lengthy route of thought, exchanging information directly via the short cut of touching nerves and tendons, thermal and metabolic systems. The act of riding means that command data is transferred in the form of physical data, in a direct exchange of sensory messages. Riding is the connection of two warm, breathing, pulsating bodies, mediated only by a saddle, a blanket or mere bare skin. Humans enter into similar informational connections when they dance together, wrestle or embrace.

Of course all you have to do is brag about your distress tolerance one time and the panic attacks come back.

There’s definitely a component of “I’m in a safe place to process shit, so shit’s coming up” going on. I’m trying to write about Australia and (surprise!) I have a lot of complicated feelings to untangle about Australia. I need to talk about it in a kind of Darmok way because it’s not rational, or linear, or English.

A book I think about all the time is Jane Jeong Trenka’s The Language of Blood, a memoir of finding your birth mother in Korea and then losing her to cancer, before you have time to learn enough Korean to say what you need to say. My mother and I didn’t communicate very well until very close to the end, when I had slowly, painfully taught myself enough about kindness to counteract my habitual ruthlessness. Immigrants are ruthless, my mother included. We jettison the past. We buckle ourselves into the geographical cure, and we don’t look back. If you look back, you turn to salt.

My bitterest memories of living in Australia are memories of living with untreated, out-of-control mental illness. What I’m feeling now are body-memories of the days when I had panic attacks 24/7. In Ireland, I found some distance (“some” = the width of the planet); in California, I found SSRIs. Now at last I can let myself understand what I gave up in exchange for these: the outlines of sacred animals on the high rocks, the Southern stars, the smell of eucalyptus trees hot under the summer sun. A landscape that made sense to me somewhere deeper than language.

We walked out of the airport terminal into a wall of humidity and cicada song. I had forgotten how good Australian summer smells. I see it now in a way I never could before I left. The ferry ride to Cockatoo Island through a working harbour surrounded by old-money waterfront property. (My family’s steadfast refusal to laugh as I called it Cockapoo Island and claimed that it was made entirely of cockapoos.) Inner western suburbs with their beautiful brick terrace houses and bullnose verandahs and tall and spreading trees. Oyster leases on the Hawkesbury. I can feel my own settler-colonial culture as a shallow, temporary film over this weirdly ancient place. My family has been here for nearly 250 years. The Aboriginal people have been here for 250 times as long.

In Barraba now, I am haunted by my parents. Here’s my mother’s craft studio. There’s where Dad had his market stall. In front of the doctor’s office is where I broke down when Dad said he was sure Mum’s cancer was cured. Last night I sat on their front porch while galahs and lorikeets threw a sunset dance party. Petrichor, all around. Behind me a sun shower and in front of me, rainbow’s end. Today, my brother and I took two cars and a whole expedition party out to Horton Falls. We surprised mobs of kangaroos. We had both forgotten to check if we had full tanks. It’s alarming to drive on a single-width bush track with the fuel light on. We glided back into town as smoothly as we could, running on fumes. But here we are.

Hashtag best summer ever continues. We went to the Berkeley Kite Festival, where Alain and I flew a kite in memory of our Dad. Dad made this particular kite for me – it must be nearly forty years old – and it ran up into the wind like it was impatient to fly again. Then we ate spicy spicy food at Vik’s Chaat House and ran over to the Oakland Museum of California. “It’s inside out,” Jeremy explained to the kids. “Inside the building is where you buy tickets, and outside is all of California.”

It’s a jewel of a place and we’ll be back, but y’all should hurry up and see the Dorothea Lange exhibit that closes on August 27. Migrant Mother is there, of course, but so are a dozen less-well-known images with the same power to cut you to the bone. Especially painful is the series on the Japanese internments, so humanizing of its subjects that despite being commissioned by the government, it was suppressed for the duration of the war. An accompanying film remarks on the behavior of the internees: “They were trying to be good citizens.”

Yesterday we visited the Cable Car Museum which, like La Brea, is a great big overdone metaphor for its hometown. To start with, there are the vast wheels turning underground, drawing citizens inexorably uphill. San Francisco, clockwork city. But it’s even worse than that. As in LA, auto, oil and rubber interests tried to get rid of urban transit systems after the war, but in SF this sparked a citizen’s revolt. Furious activism saved the cable cars and now they are protected in perpetuity, to be an overpriced tourist attraction.

Ridiculous city, how I love you. This was a Pyrrhic victory maybe, but one that paved the way for the future citizen activists who tore down freeways and helped find treatments for AIDS. They say it’s science fiction that’s the fantasy of political agency but it’s also true of the other SF.

Alain wanted to visit Legoland, so I plotted a route to Carlsbad that took in La Brea on the way. I was about 13 when Dad came home from a business trip to LA, overflowing with excitement about the tar pits, the dire wolves and the saber tooths, the bison, the sloths and oh my God, the mastodons.

I went looking for that Dad, of course. Young Dad, enthusiastic Dad, the Dad who brought the world to life for me. He isn’t there, what with being dead and all, but he was less not-there than usual. Having Alain with me was part of it. Another part was seeing Oscar Isaac in Hamlet a couple of weeks ago, sitting at his dead father’s feet with his head bowed. I cried for his grief as I’ve been unable to cry for my own.

It’s hard to make fossils, but in the tar pits, the conditions are just right. This display includes less than a tenth of the dire wolf skulls alone. La Brea’s full yield is in the hundreds of thousands. My own tar pits, the darknesses that pull me under, are likewise rich in ice age bone jumbles. My job is to uncover them with care, and to document the shit out of them.

The original acts of colonization and violence broke the world, broke our hearts, broke the connection between soul and flesh. For many of us, this trauma happens again in each generation

“This is literally just a kick drum and a synth.”

“In the nineties we didn’t have any musical instruments.”

“Yes you did.”

“We had two skateboards in the entire world. We had to share.”

“Mama.”

“There were only eleven of us.”

“And you were all green.”

“Yes. We were all green.”

Marching in the cold rain, my END WHITE SUPREMACY sign sagging, my husband and children festooned with glowstick necklaces, my city jammed with peaceful protestors from Civic Center to the Ferry Building: Market Street one river of loving souls.

The next day, beyond exhausted, crashed out on the couch; shy Alice making her way up onto my chest, quietly as if I might not notice, then crashing out there with me for most of the afternoon. Her fur from which no light escapes. The soft floof that grows out between her toe beans.

Driving up Bernal Hill with Liz to enjoy the raggedy clouds and dramatic light and rainbows. Stopping in silence at Alex Nieto’s memorial, a landslide of flowers.

An emergency drill at NERT to teach us how to self-organize and keep records. Head down counting people in and out of Logistics as incident after incident came in to Planning and Operations; adrenaline and worry and focus and exhilaration. When we got through it, high-fives all round.

At the exquisitely restored Curran Theatre to see Fun Home with my wife and our kids (it’s great; you should go.) The audience filled with lesbians a generation older than us; the ones who cared for men dying of AIDS; my angels, the saints of our city. May I walk in their sacred footsteps.

“I keep thinking there’s a beach at the end of this,” a friend said. “An island, and we’ll be happy again.”

His mother left yesterday after his cremation and when I walked her to the cab, she said to me: ‘I think the reason I was put on earth was for these last two months.’”

One cannot expect people to live in a state of perpetual horror and outrage. Eventually they subside. Fatigue sets in, burnout, boredom, acceptance—and the attention span turns to something else. How could it be otherwise? Yet all of this is strange.