insurgent empire, by priyamvada gopal

Common ground, even shared human feeling, is not a given, but is arrived at through imaginative work.

Common ground, even shared human feeling, is not a given, but is arrived at through imaginative work.

Posted in bookmaggot | Comments Off on insurgent empire, by priyamvada gopal

I think of the future I thought I was going to have and the one yawning in front of me like a chasm.

Posted in bookmaggot | Comments Off on the cruel prince, by holly black

That’s basically the story of every woman’s life, right? You become your mother or you don’t. Of course, every woman says she doesn’t want to be her mother, but that’s foolish. For a lot of women, becoming their mothers simply means growing up, taking on responsibility, acting like an adult is supposed to act.

Posted in bookmaggot | Comments Off on lady in the lake, by laura lippman

The trouble is a deep unawareness, and a wish to remain unaware, of the experience of living here, now.

Posted in australia, bookmaggot | Comments Off on the australian ugliness, by robin boyd

Something changed in the world. Not too long ago, it changed, and we know it. We don’t know how to explain it yet, but I think we all can feel it, somewhere deep in our gut or in our brain circuits. We feel time differently. No one has quite been able to capture what is happening or say why.

Posted in bookmaggot, grief | Comments Off on lost children archive, by valeria luiselli

“The computerization of society,” the technology writer Frank Rose later observed, was essentially a “side effect of the computerization of war.”

Posted in bookmaggot, grief | Comments Off on command and control, by eric schlosser

If you find yourself drawn toward the tendency to help or “do something,” you might instead work to increase your capacity to sit with others’ suffering

Posted in bookmaggot, grief | Comments Off on ancestral medicine, by daniel foor

It seems unfortunate, but nothing was learned from the Chernobyl disaster.

Posted in bookmaggot, history | Comments Off on atomic accidents, by jim mahaffey

even today we do not know which of the strategies the Soviets tried and the technical solutions they implemented actually worked. Could some of them have made things worse?

Posted in bookmaggot, history | Comments Off on chernobyl, by serhii plokhy

…atrocities such as the Rape of Nanking can be seen as a predictable if not inevitable outgrowth of ceding to an authoritarian regime

Posted in bookmaggot, grief, history | Comments Off on the rape of nanking, by iris chang

I thought I understood the fact of my mother’s impending death, but I had not. I had no idea of the feelings and fears and complications, the pit opening up before me, the loss of the key to my identity.

Posted in bookmaggot, grief | Comments Off on old in art school, by nell irvin painter

You’ve also stayed away because you’ve discovered how easy it is to cut her loose, how little you actually miss her

Posted in bookmaggot, grief | Comments Off on history of violence, by édouard louis

I am done. Your grief will be useful some day, says no one.

Posted in bookmaggot, grief | Comments Off on prelude to bruise, by saeed jones

All you people do, wherever you are in this world, is just bring death and destruction, you bring nothing good, nothing good

Posted in bookmaggot, grief | Comments Off on speak no evil, by uzodinma iweala

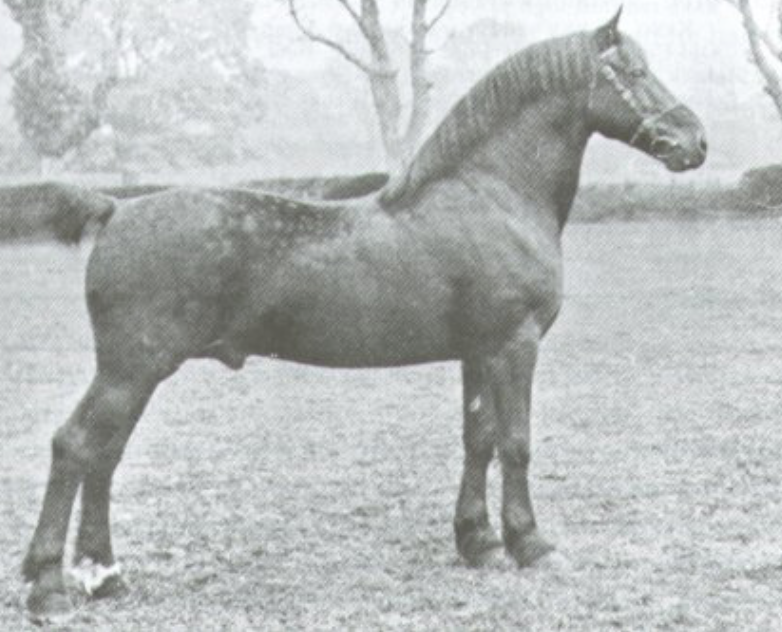

Last night I read and enjoyed Wynne Davies’ The Welsh Cob, described in Amazon reviews as “for cob enthusiasts only”. (I feel seen.) While there have been horses in Wales since pre-Roman times, the purebred cob, an absolute unit, is a surprisingly late invention. The first Welsh stud book was published in 1902, following a busy late 19th century of outcrossing native Welsh ponies with Thoroughbreds, Arabs, Hackneys, Norfolk Roadsters, and Yorkshire Coach Horses.

King Flyer, b1894

At almost exactly the same time, my old friend Lady Anne Blunt was importing Arabian horses to England. The modern Arabian and the Welsh Cob were modeled on the English Thoroughbred, itself a literary fiction. Horses, obviously, exist, but purebred horses exist only in books, beginning with the General Stud Book of 1793. The GSB represents a cartel of Thoroughbred breeders and owners. Only horses registered in the GSB can race on the flat in Britain. A closed stud book raises prices by creating artificial scarcity. (Because of the risk of fraud, Thoroughbreds can only be registered if they are conceived by “live cover”, rather than artificial insemination, a quirk of history that keeps a lot of Thoroughbred stallions very busy.)

The GSB is almost exactly contemporaneous with the United States of America, and both of them pre-date Burke’s Peerage, the stud book for British humans. Nations are also literary fictions. Different rules apply to those whose names are written down in the right books. The white colonists needed a reason to argue that while they deserved liberty from oppression, their slaves did not. They found it in the invention of race. White people, like Thoroughbred horses, counted. They were counted. Black people, like half-bred horses, counted for less. Purebred horses were invented in part as a way to make this appear to be a law of nature: but it isn’t.

Posted in bookmaggot, history, horses are pretty, politics, ranty | Comments Off on the invention of horses

She demeaned her own constant reading as “little more than a drug habit.”

Posted in bookmaggot | Comments Off on prairie fires, by caroline fraser

“I . . . am waiting among the dead for death to come.”

Posted in bookmaggot | Comments Off on the great mortality, by john kelly

He took the Parisians to the limestone quarry, where they could see that their city was an immense mass grave of long-since annihilated creatures. As they had gone under, so would we ourselves, their descendants, go under.

Posted in bookmaggot | Comments Off on the dead do not die, by sven lindqvist

We used to have this self-centered idea that Western democracies were the end point of evolution, and we’re dealing from a position of strength, and people are becoming like us. It’s not that way. Because if you think this thing we have here isn’t fragile you are kidding yourself.

Posted in bookmaggot | Comments Off on nothing is true and everything is possible, by peter pomerantsev

We spent the weekend in Point Reyes, which is so beautiful it almost defies photography. The California Field Atlas describes it as an authentic Pleistocene-era prairie by the sea. Philip K. Dick was also moved by:

this wild moor-like plateau that dropped off at the ocean’s edge, one of the most desolate parts of the United States, with weather unlike that of any other part of California.

The giant camels and mastodon that roamed here in the Ice Age are gone, but if you look closely, there’s a herd of not-quite-extinct tule elk grazing out on this headland.

Jeremy was enchanted by the Marconi RCA wireless station, the first and last of its kind. Now that we are home, he’s in his office playing with software-defined radios and emitting atmospheric bursts and Morse code. For my part, I loved the dairy ranches, and imagined myself quitting tech to become a simple farmer, a man of the people, at one with the land.

Of course I am not the first to indulge this fantasy. It forms the substance of Dick’s Confessions of a Crap Artist, Daniel Gumbiner’s The Boatbuilder, and even Summer Brennan’s The Oyster War. All three are at pains to point out that no matter how lovely the place is, it can’t help you escape who you are.

West Marin has dangled before the white mind like a lure for almost five hundred years. In 1579, the pirate Francis Drake in his galleon full of stolen Spanish treasure christened it Nova Albion and claimed it for Queen Elizabeth I. The visitor center on Drakes Beach notes that people in South America used his name to frighten their children, so that’s nice.

The Coast Miwok survive and now form part of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria. Still, anthropologist Betty Goerke calculates that between genocide, epidemic, and aggressive zoning laws designed to maintain high property values, there are fewer people living in Point Reyes today than there were in Drake’s time. It’s a pretend wilderness, like Yosemite and Kur-ring-gai. I’m indebted to its original custodians for how it heals my sore heart.

Posted in adventure time, bookmaggot, little gorgeous things, mindfulness | Comments Off on by the sea shore

© 2009 “Yatima” · Powered by Wordpress and Bering Theme 2025