craft for a dry lake, by kim mahood

There was a time when the notion of beauty would not have entered my head, when it was simply my place. I did not know it was beautiful

There was a time when the notion of beauty would not have entered my head, when it was simply my place. I did not know it was beautiful

We enjoyed the Rivercat so much that we’ve taken two more ferries, one around Scotland Island from Church Point and one to the Basin from Palm Beach. Pittwater smells of salt and diesel, the smell of my childhood. There are cormorants and kookaburras, gulls and jellies.

I read this remarkable essay about Australian childrens’ books as well as a thoughtful article about the high country brumbies that I can’t share because it’s paywalled to hell. Like the mustangs in California, Australia’s feral horses wreck delicate ecosystems. Scientists and the traditional owners of country want them gone. But local cattlemen lost grazing land to the Snowy hydro scheme and to the National Parks well within living memory. To them, the brumby cull is the last straw. In the paywalled article, National Party MP Peter Cochran whines: “You don’t have to be black to feel a connection to this land.”

I grew up on stories about brumbies, by Mary Elwyn Patchett and Elyne Mitchell. In them, the wild horse is as much a part of the bush as the possum and the kangaroo. It took me decades to recognize this as a way for white people to lay claim to what wasn’t theirs. When I revisited Patchett hoping to read her books to the kids, I was appalled by her racism. Mitchell’s father was Harry Chauvel of the charge on Beersheba. Both writers are immersed and complicit in the white supremacist, militarized, settler-colonialist narrative that Evelyn Araluen describes in her essay.

Even my beloved Swallows and Amazons, with its naval officer father and its mother who grew up sailing on Sydney Harbour, instructs children in exploration, mapping and conquest. Maybe Westerners can’t have innocent pleasures. There is nothing – absolutely nothing – half so much worth questioning as simply messing about in boats. Do you want empires? Because that’s how you get empires.

I miss Port Jackson a lot; people who say that the Bay is like it don’t seem to know either of them very well.

Last year we went to Cockatoo Island. This year we decided to keep going, as far as we possibly could, all the way to Parramatta. It was very hot and we all got sunburned and this is the cover of our next album.

I expected something vaguely industrial from the Parramatta River. Instead I got mangroves and casuarinas, pelicans and ibis.

Sydney is so enormously full of surprises that I do not think I will ever come to the end of it.

I wrapped up a mighty four weeks at work before skiving off on (previously-scheduled) hols. My signature achievement so far is having matched names to faces for my boss’s eighteen direct reports. If you think I’ll retain that mapping after a fortnight sitting on Sydney beaches eating mangos, I have several bridges you might like to purchase.

This was my first time flying with my brand new cyborg leg. Despite what my doctors told me, it does indeed set off the metal detectors. I was frisked around the scar tissue, which was very interesting. Otherwise our flights were uneventful. You walk out of the Sydney international terminal into a wall of southern hemisphere summer and if you are me, it brings tears to your eyes.

Of course all you have to do is brag about your distress tolerance one time and the panic attacks come back.

There’s definitely a component of “I’m in a safe place to process shit, so shit’s coming up” going on. I’m trying to write about Australia and (surprise!) I have a lot of complicated feelings to untangle about Australia. I need to talk about it in a kind of Darmok way because it’s not rational, or linear, or English.

A book I think about all the time is Jane Jeong Trenka’s The Language of Blood, a memoir of finding your birth mother in Korea and then losing her to cancer, before you have time to learn enough Korean to say what you need to say. My mother and I didn’t communicate very well until very close to the end, when I had slowly, painfully taught myself enough about kindness to counteract my habitual ruthlessness. Immigrants are ruthless, my mother included. We jettison the past. We buckle ourselves into the geographical cure, and we don’t look back. If you look back, you turn to salt.

My bitterest memories of living in Australia are memories of living with untreated, out-of-control mental illness. What I’m feeling now are body-memories of the days when I had panic attacks 24/7. In Ireland, I found some distance (“some” = the width of the planet); in California, I found SSRIs. Now at last I can let myself understand what I gave up in exchange for these: the outlines of sacred animals on the high rocks, the Southern stars, the smell of eucalyptus trees hot under the summer sun. A landscape that made sense to me somewhere deeper than language.

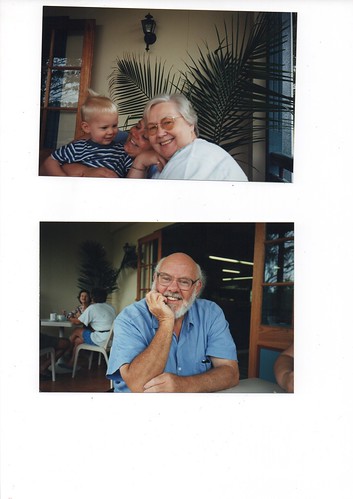

This one is for all the other adult orphans out there. Yesterday was the third anniversary of Dad’s death. Tuesday is the fourth anniversary of Mum’s. I call this Shark Week and even though I don’t believe in astrology or the significance of dates, I always find myself glum.

That’s all right though. When I was younger and recovering from depression, I was flinchy around any negative emotion, in case it dragged me down into the dark again. But with age and having watched a lot of sad movies (on dates that Jeremy and I like to call distress tolerance dinner theatre) comes the ability to sit with my grief and not try to stuff it away in a box so much.

I will be 47 this month, and it turns out that I can think about Jean and Robin and how complicated and flawed and wonderful they were, and how their awkward and hilarious and tragic love affair is literally what I am made of, and have a bloody good cry about it, and not die.

currawongs are intelligent, resourceful, adaptable and utterly loveable (affectionate, patient and accommodating – those who have raised one or two will know what I mean)

We walked out of the airport terminal into a wall of humidity and cicada song. I had forgotten how good Australian summer smells. I see it now in a way I never could before I left. The ferry ride to Cockatoo Island through a working harbour surrounded by old-money waterfront property. (My family’s steadfast refusal to laugh as I called it Cockapoo Island and claimed that it was made entirely of cockapoos.) Inner western suburbs with their beautiful brick terrace houses and bullnose verandahs and tall and spreading trees. Oyster leases on the Hawkesbury. I can feel my own settler-colonial culture as a shallow, temporary film over this weirdly ancient place. My family has been here for nearly 250 years. The Aboriginal people have been here for 250 times as long.

In Barraba now, I am haunted by my parents. Here’s my mother’s craft studio. There’s where Dad had his market stall. In front of the doctor’s office is where I broke down when Dad said he was sure Mum’s cancer was cured. Last night I sat on their front porch while galahs and lorikeets threw a sunset dance party. Petrichor, all around. Behind me a sun shower and in front of me, rainbow’s end. Today, my brother and I took two cars and a whole expedition party out to Horton Falls. We surprised mobs of kangaroos. We had both forgotten to check if we had full tanks. It’s alarming to drive on a single-width bush track with the fuel light on. We glided back into town as smoothly as we could, running on fumes. But here we are.

…‘desert’ is a term Europeans use to describe areas where they can’t grow wheat and sheep.

In time, a long time, bark and branch will conceal the scars as though they never were. Some eucalypts are much older than we imagine.

The water has changed. Once it ran slower and clearer. The Darling below Bourke was ‘beautifully transparent, the bottom was visible at great depths, showing large fishes in shoals, floating like birds in mid-air’.

People today think of what animals need. In 1788 people thought of what animals prefer. This is a crucial difference.

The southern hemisphere is not a mirror image of the north.

the crows approached the female banteng, somehow indicating their intention. The banteng female then rolled onto her back and held her legs up, straining to hold her position, so that the crows could get to the belly and the area between belly and leg. The crows then proceeded to quickly peck at the exposed areas, the authors assuming that the crows extracted ticks and the cow then rolled back onto her belly.

Here is a bird exceptionally endowed for song and yet so much of what is produced seems to have no easily identifiable function.

In Sydney, after a fairly peaceful flight, a day of intractable jetlag and a night of proper sleep. All four of us are on our devices on the bed in Jeremy’s and my room, watching the sky lighten behind the ferns on the patio, girding our loins to head over to the little cafe we like. It is humid. I’m reading Kim Mahood’s Position Doubtful, which is unlike any other book I have ever read.

In fact, despite my breaking away, I haven’t gone very far.

The world in the meantime had not improved; in fact it had become crueler for women.

Lots of them, in fact. Snow in Central Park. Laughing, giddy, with Leonard and Sumana and Brendan and Kat and Claire and Julia, saying “What do you wanna do now? Shall we go see that show, what’s it called, the one about Hamilton? Yeah, let’s go see Hamilton!” Sitting around the evening campfires on Diamond Beach, toasting Mum and Dad with gin and tonic and love. Walking into La Sagrada Familia and feeling my knees buckle. Christmas Eve, when we saw the Bernal coyote, her golden eyes, her wild face. And every single moment with Sam Horse, my wisest, kindest teacher since last January 1.

When I went back to church in November, I chose an Episcopalian (Anglican) church because of a dark wave of rage and grief and protest that rose inside me, to the effect that it was my mother’s church and her mother’s church before her, and terrible men tried to take it from me, and they can’t have it, because it’s mine. So too this year. So, too, my life.

If there was no war then thousands of Aborigines were murdered in a centurylong, continent-wide crime wave tolerated by government. There seems to be no other option. It must be one or the other.

A fresh new irony in my life is that I have become fascinated with Aboriginal rock engravings, 20 years after leaving Sydney where they are present in magnificent abundance, 25 years after graduating from the Department of Archaeology where John Clegg taught and a year after John Clegg’s death. I never could see the precious things that were right in front of my face.

This one’s a little hard to make out, but it’s a whale shark, its nose pointing to the left, two eyes on the white patch of rock, and a fish inside it, its nose pointing down. It’s on the cliffs above Tamarama, on the spectacular walking path from Bondi to Coogee. We walked up there one late afternoon as the sun set behind the city and set the sky on fire.

The next two turned out beautifully – we found them at blazing high noon – but the shaming part is, they are part of an incredibly rich field that is walking distance from my childhood home, on a track I regularly wandered down, but I didn’t even notice that they were there until shortly before I left the country for good. They weren’t signposted as they are now, but also, I just wasn’t paying attention.

I remember a visitor from England saying very snottily that he couldn’t live in Australia because there wasn’t enough history here, compared with where he grew up. I wish I’d known enough to drag him to this place and point out that the people who made this art lived peacefully on this land for 40,000 years before there even was an England.

Murri stockman Herb Wharton wrote:

The old tribal elder who had spoken before said that he did not trust people who could leave the place where they had been born, to go to another country. For him, for all of them, their land was their mother, a sacred place. No matter what injustices they had suffered, nothing could ever break that tie with their own land and with the Dreamtime. Yet every one of this boat mob had left his own land.

I am boat mob twice over – my English mother, my exile self.

This site was the hardest to find and the most beautiful. Again, it was a few metres off a bush track I knew well, where I used to let my Arab horse Alfie stretch out and gallop; almost exactly halfway between my godmother’s house and that of Jeremy’s Aunty Jan. The kids were incredibly patient as I searched and searched for the obscured beginning of the footpath, and uncomplaining about the spiky grass and prickles they endured along its length. When we finally found the site it was as obviously holy a place as any church.

It’s believed to celebrate a successful hunt; that’s a spear between the kangaroo’s shoulder blades. I think your family of choice includes ancestors of choice as well. You choose which writers and painters and musicians and activists you want to emulate, and which you don’t. I recognize the people who made these images and the people who work to protect them. I acknowledge them as parts of myself, debts to ancestors I never knew, a motherland that will not leave me no matter how often I leave it.

One night she watched the tram light coming towards her, the rails gleaming, the road slick with rain. The trams had been a little adventure in the beginning but now they were the emblem of the hard machine of her days. I could step out in front of it, she thought. That would put an end to the misery and the loneliness and the feeling that every day would be like this forever. It would hurt, she supposed. But if she was lucky it would all be over in a second. In the moment she stood with that choice, she was free of everyone else in the world…

We braved the Metro (Jeremy deftly blocking a pickpocketing attempt) out to Parc de la Villette to visit the Cité des Sciences et l’Industrie, which according to Wikipedia is the biggest science museum in Europe. It is pretty big! We bought tickets to all the temporary exhibitions, which was a bit of a misstep because the permanent exhibitions were exquisite and we didn’t get to spend anywhere near enough time with them.

As we were touring the Argonaut, a decommissioned submarine, I got mail from the neuroscientist in London who is writing the case study about Dad’s blog. We had hoped to move Dad’s brain to a brain bank for further study but unfortunately this won’t be possible. The neuroscientist reassured us that although Dad’s brain has already been embalmed and used to train surgeons, the resulting anatomical report will still be very helpful in establishing the diagnosis of fronto-temporal dementia.

Dad used to take us to the Observatory and the Australian Museum and the Powerhouse and its precursor, the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, all the time. He took us to Taronga and Western Plains Zoo and Tidbinbilla and Parkes. His factory built fire control systems for the Collins Class submarine. He would have loved the Cité. I feel a space where grief should be. Proposed Site for Grief. What happened to Dad is so huge and terrible I can’t even get there yet. All I have is these tiny, inadequate glimmers of what he was. Of all that we have lost.

Maybe 2000 or so? Sarah guesses Mt Coot-tha, ’97 or ’98. That’s Original Dad for sure.